We can see Bitcoin as a peer-to-peer network of cooperating nodes. These nodes listen for transactions, order them into subsequent blocks, and then publish these blocks on the network. The network uses digital signatures to verify the ownership of funds, and a Proof-of-Work system based on hashing to prevent double-spending. These techniques bring trust to the whole history of transactions, which in turn allows users to exchange value. Let us now unveil how all this works.

Brief History

The initial era of Bitcoin is rather mysterious. The domain bitcoin.org was registered on 18 August 2008. On 31 October, Satoshi Nakamoto, whose identity remains unknown, published a paper describing a peer-to-peer electronic cash system named Bitcoin (Nakamoto 2008), and subsequently released an open-source implementation. On 3 January 2009, the genesis block was mined,1 bringing the Bitcoin network into existence. The first Bitcoin transaction was made on 12 January 2009. Since then, the codebase has been growing, and Satoshi Nakamoto completely disappeared from the Internet.

The network has not experienced a single outage since its inception. At the time of writing, there are thousands of Bitcoin nodes operating worldwide, making the network reliable and robust. These nodes are run by volunteers since Bitcoin has no central authority. Besides experiencing no outage, there has been no successful attack on the Bitcoin blockchain that would deprive the owner of the funds they possess.

Bitcoin Protocol

The system is designed so that there is no need for a trusted authority. This is accomplished by introducing a Proof-of-Work system alongside a data structure later identified as the blockchain.

The network protocol operates by following these steps:

- New transactions are broadcast in the network by clients.

- Nodes gather incoming transactions into a block.

- Each node starts finding a Proof-of-Work for the block currently being created.

- Once any node finds the Proof-of-Work for the block, the node broadcasts the block in the network.

- Other nodes accept this block only if all transactions in it are valid and not already spent.

- Nodes express their acceptance of the block by starting to create another block on top of the received one, including the hash of the received block in the new one.

Hash Functions

Before we can discuss transactions and blocks, we need to briefly introduce hash functions. A hash function takes an input of any size and produces a fixed-size output called a hash. Equal inputs naturally produce equal outputs, but the most important property is that changing any bit in the input makes the function produce a completely different output.

Hash functions are an elementary building block in cryptography, and we call them a cryptographic primitive. Cryptocurrencies rely on many different cryptographic primitives, which is why people started calling them cryptocurrencies.

Integrity Checks

If you download an app to your phone from the internet, your phone will run it through a hash function and compare the result to a hash provided by the server. If the hashes match, your phone can be sure every bit in the downloaded app is correct and that nobody injected anything malicious during the transmission. This is called an integrity check. On the other hand, if even a single bit is off, you will get a completely different hash. The hash functions used in practice are so good that about half the output bits will randomly flip if you flip a single bit in the input.

Irreversibility

Another important property is that given only the output, there is no way to reconstruct the input. Hash functions are irreversible, meaning that the output tells you nothing about the input. You can think of them as one-way functions: if someone gives you an input, you can compute its hash easily, but if they give you a hash and ask for an input that produces it, you will not be able to oblige.

Reversing an irreversible hash function might seem paradoxical, yet that is essentially what miners do. They repeatedly try enormous amounts of inputs as fast as they can until they hit a hash the network needs. This is the most naive way of obtaining the correct input, and the approach is called brute force. If brute-forcing is the only way to solve a problem, we call the problem computationally hard. Since hash functions are irreversible, reversing them is computationally hard.

Collision Resistance

Since hash functions accept arbitrary inputs and produce fixed-size outputs, they map an infinite set to a finite one. Strictly speaking, there is an infinite number of inputs that lead to the same output for each hash function. Although this is theoretically true, we may neglect it in practice and pretend that no two inputs lead to the same output, or at least that it is impossible to find such two inputs. We call such hash functions collision-resistant.

The reason we can afford collision resistance is the size of the set of possible hash values. We typically use at least 256 bits for the output. There are \(2^{256}\)2 256 ways to arrange the 256 zeroes and ones, yielding \(2^{256}\)2 256 distinct hash values. For intuition, there are only around a thousand times more atoms in the visible universe. Using such an astronomically large output space makes finding two colliding inputs practically impossible, even though we know collisions theoretically exist. The same reasoning applies to private keys.

The last two properties we care about are that you cannot predict what the output will look like unless you run the function, and running the function is fast. If you want to get a hash of your data, the only way is to compute it, and you will get the result in under a millisecond.

Wallets and Addresses

Before discussing actual transactions, it is worth mentioning that a Bitcoin wallet can be thought of as a public/private key pair. A user can generate an arbitrary number of such key pairs, meaning one user can hold any number of wallets.

A user generates a key pair on their own. This key pair is regarded as a wallet, and the public key of the key pair is regarded as the address of the wallet. The private key is kept secret and is used to manage the funds belonging to the wallet. The user then shares the address so other users who possess some bitcoin can send funds to this address by broadcasting a transaction that will either be accepted and written to the blockchain (only if it is a valid transaction) or simply ignored. This process is thoroughly described in the Chain of Transactions and Chain of Blocks sections. Besides mining, there is no other way for new bitcoin to enter circulation. Note that there is no need to register anywhere. Also note that all the user needs in order to access the funds is the key pair. This means that the user is not bound to any device while using Bitcoin. The user can generate a new wallet on their phone (even with no internet connection), share the address of the wallet, retain the key pair, and then destroy the phone. The user can also subsequently travel to the other side of the world with just the key pair and then use it to access their funds on any device with internet access and a Bitcoin client installed. This is possible due to the public nature of the blockchain described later on. However, if the user loses the private key, the funds are lost forever. Also, once the private key is exposed to an adversary, that adversary instantly gains full control over the funds.

Another property of Bitcoin is that transactions are irreversible. This means that once funds are sent to the wrong address (even an address for which no one knows the private key), and this transaction is written to the blockchain, there is no way to reverse it.

A legacy Bitcoin address is a Base58Check-encoded string of 25 to 34 characters,

beginning with 1 (Pay-to-Public-Key-Hash) or 3 (Pay-to-Script-Hash). Base58Check excludes the uppercase letter O, uppercase

letter I, lowercase letter l, and the digit 0 to prevent visual

ambiguity. Native SegWit addresses begin with the prefix bc1 and are

Bech32-encoded, making them case-insensitive and between 42 and 62 characters

long. Examples of Bitcoin addresses:

1BvBMSEYstWetqTFn5Au4m4GFg7xJaNVN2

bc1qar0srrr7xfkvy5l643lydnw9re59gtzzwf5mdq

Modern Bitcoin clients (often called simply wallets) implement a hierarchical deterministic (HD) wallet for deriving the key pairs from a seed (Wuille 2012). This approach makes Bitcoin wallets more user-friendly while having no impact on the Bitcoin network. The seed is a random 128-bit number that can be encoded into a human-readable format called a seed phrase, which consists of 12 English words that the user has to retain. The wallet can then deterministically create an unlimited number of addresses. The same seed can also be used on multiple devices so the user can control the exact set of addresses on any of these devices. The user doesn’t have to retain any of the private keys. It is crucial to generate the seed in a truly random fashion to prevent a collision with another seed. In the case of a collision, both users would end up with the exact same key pairs, which would be catastrophic.

Privacy

Bitcoin cannot be considered private nor untraceable since all of its transactions (containing public keys and bitcoin amounts) are public, and it is possible to track them not only backwards but also forwards. This means that if we focus on a certain address or transaction, we can trace all the previous transactions as well as observe the future ones. It is also possible to see how much funds each address holds — there are online blockchain explorers that offer all the details at a glance to anyone. One such explorer is blockchain.com/explorer. If we manage to associate someone’s identity with a certain address, the privacy of that user is lost. The information about the complete transaction history is immutably and publicly stored in the blockchain forever.

In order to make transactions private and untraceable, one can utilize zero-knowledge cryptography (Ben-Sasson et al. 2014, 2015). Bitcoin does not implement these techniques, but some other cryptocurrencies do.

It is recommended to generate a new address for every transaction, and wallets typically generate fresh addresses for each payment request or invoice. Even when a user sends only a fraction of the funds they hold on a particular address, the source address is usually fully withdrawn, and the change is sent to a newly generated address that belongs to the sender. This is done automatically by the wallet. These methods make tracing more difficult.

It is possible to prevent potential network surveillance or censorship by using the Tor anonymity network for connecting to the Bitcoin network. Some wallets have this functionality built in.

Chain of Transactions

All transactions in the network are public, and anyone can verify their validity. Transactions in Bitcoin have the following content (simplified):

- hash of itself

- Every transaction is identified by its hash. The implementation uses SHA-256.

- input

- Contains the following:

- previous transaction: A hash referencing the previous transaction.

- signature: The hash of the current transaction signed with the private key of the owner.

- output

- Contains the following:

- value: The amount of bitcoin that the sender is willing to send.

- receiver’s address: The public key of the receiver’s Bitcoin address.

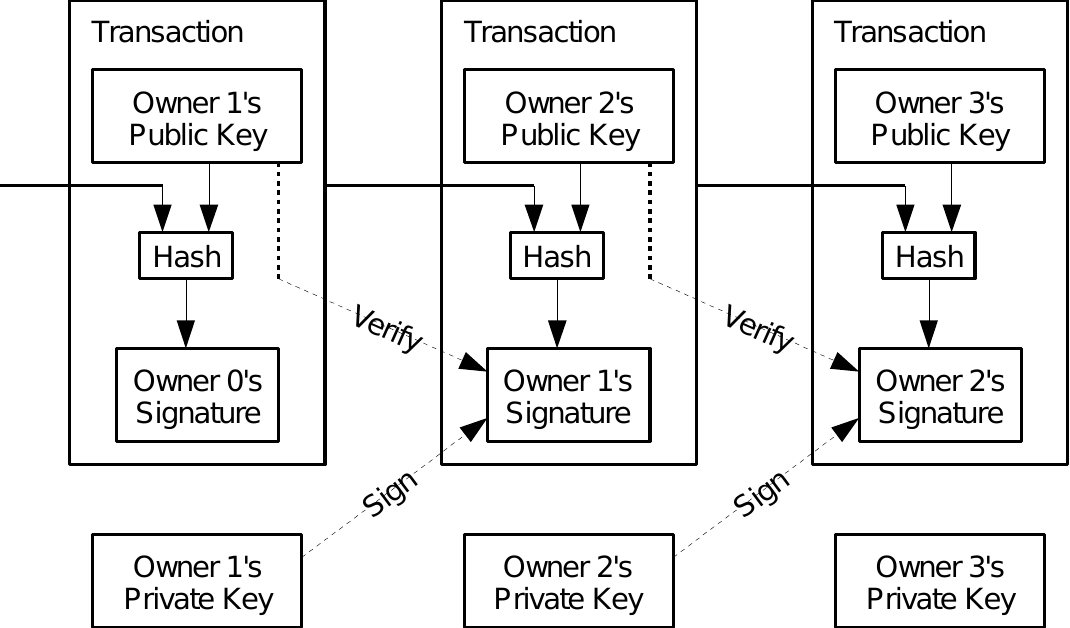

This transaction structure creates a chain of transactions since the input references the previous transaction. We can notice that the transaction also contains the receiver’s address and that the whole transaction is signed (containing the hash of the previous transaction). This in fact creates a chain of trust — the receiver (and anyone else) can verify that the sender owned the funds that are being sent in the following way:

The receiver looks at the transaction referenced in the input and gets the sender’s public key from it. Subsequently, they verify that the signature of the current transaction is valid. If this is true, we can be sure that the funds are transferred (to the owner of the public key specified in the output) only by the owner of the private key that corresponds to the public key stored in the output of the referenced previous transaction.

A simplified chain of transactions is depicted in Figure bb.

Figure bb. Outline of transactions and their ordering (Nakamoto 2008).

Transactions can have multiple inputs and multiple outputs. This allows the value to be split and combined. All inputs are summed up, and this sum has to be spent in the outputs.2 If we don’t want to use all the funds specified in the input, we can simply send them back to the same wallet that we currently use for the transfer.

The approach described above doesn’t rule out double-spending. The owner could transfer their funds multiple times. To prevent this, we could introduce a global authority that would check every transaction. Bitcoin addresses this issue without such an authority.

Cryptographic Primitives

The current implementation of Bitcoin utilizes the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA); however, it would also be possible to use other algorithms such as the Schnorr signature algorithm. The description of ECDSA can be found in (Brown 2009). The algorithm employs the secp256k1 elliptic curve defined in (Brown 2010). ECDSA is based on the discrete logarithm problem for which there is no known algorithm that solves the problem on a classical computer in polynomial time. In general, it is a function problem, and if formulated as a decision problem, it can be shown that it belongs to the \(\mathcal{NP}\)NP complexity class. It can also be shown that the problem belongs to the bounded-error quantum polynomial time (\(\mathcal{BQP}\)BQP) complexity class. This means that if humans ever manage to build a quantum computer, it might be possible to solve the problem in polynomial time using Shor’s order-finding algorithm, and therefore effectively break ECDSA.

Let us now look at the underlying elliptic curve. Let \(\mathbb{F}_p\)F p be a finite field specified by the odd prime \(p\)p, and let \(a, b \in \mathbb{F}_p\). The elliptic curve \(E(\mathbb{F}_p)\)E(F p) (named secp256k1 in the standard) over the finite field \(\mathbb{F}_p\)F p is the set of solutions (which can be regarded as points) \(P = (x, y)\)P = (x, y) for \(x, y \in \mathbb{F}_p\)x, y F p that satisfy the equation: \[ E : y^2 \equiv x^3 + ax + b \pmod{p}, \] where \(a = 0\)a = 0, \(b = 7\)b = 7, and \(p = 2^{256} - 2^{32} - 2^9 - 2^8 - 2^7 - 2^6 - 2^4 - 1\). Since the coefficient \(a\)a is zero, the equation becomes \[ y^2 \equiv x^3 + 7 \pmod{p}. \] In fact, the finite field \(\mathbb{F}_p\)F p is the prime field \(\mathbb{Z}_p\)Z p with the characteristic \(p\)p. It can be easily shown that the points on the curve form an additive abelian group under the standard point addition operation. The standard also specifies the base point \(G\)G, which is a generator of a subgroup of the original group. Since the cofactor of the base point is \(1\)1, the base point actually generates the whole group. The order \(n\)n of the base point, and in fact of the whole group, is a 256-bit number. The private key in ECDSA is a randomly selected integer in the interval \([1, n-1]\)[1, n-1], and the public key is a point on the curve.

Note that a point on the curve consists of two coordinates, both of which are 256-bit numbers. However, for any \(x\)x coordinate there will only ever be two possible values of \(y\)y. We can therefore encode the \(y\)y coordinate with just a single bit. This allows us to encode any point in a compressed form that is approximately 256 bits long.

We see that the curve offers 256 bits of entropy since we have approximately \(2^{256}\)2 256 points; however, we have to consider it together with ECDSA, which is based on the discrete logarithm problem. The algorithms that solve the problem, such as the baby-step giant-step algorithm, have time complexity \(\mathcal{O}(\sqrt{n})\)O(n), where \(n\)n is the order of the group. Since \(n \approx 2^{256}\), the actual complexity is \(\mathcal{O}(\sqrt{2^{256}}) = \mathcal{O}(2^{128})\). This gives us 128 bits of security, which is equivalent to a 3072-bit RSA/DSA modulus (the size of a properly encoded public key is approximately 256 bits). We see that elliptic curve cryptography offers much shorter keys compared to RSA/DSA.

The actual Bitcoin address is a 160-bit hash of the public key. This means there are two ways a potential collision could occur. The first possibility is that two users generate the same keys, resulting in the same hash. The second possibility is that two different keys result in the same hash. Even though the keys are different, the signature will still be valid, and the users will be able to manipulate each other’s funds. The chance for any of these collisions to occur is negligible provided a true random number generator is used.

Bitcoin does not use encryption. It uses cryptography solely for digital signatures.

Script

Each transaction in Bitcoin can be regarded as a short program or a trivial smart contract — each transaction contains executable data that are executed by the node. Bitcoin uses a scripting system called Script, which is stack-oriented. It contains dozens of instructions and is intentionally not Turing-complete as it contains no instructions for jumps or loops. Such design is for security reasons — it is not possible to create a malicious transaction that would make the node stuck in an infinite loop. Table bn demonstrates some instructions. A zero value is interpreted as false.

Table bn. Common Script instructions.

| Instruction | Input | Output | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

OP_DUP | \(x\)x | \(x, x\)x, x | Duplicates the top stack item. |

OP_EQUAL | \(x_1, x_2\)x 1, x 2 | true / false | Returns 1 if the inputs are exactly equal, 0 otherwise. |

OP_VERIFY | true / false | nothing / fail | Marks the transaction as invalid if the top stack value is not true. The top stack value is removed. |

OP_EQUALVERIFY | \(x_1, x_2\)x 1, x 2 | nothing / fail | Same as OP_EQUAL, but runs OP_VERIFY afterward. |

OP_HASH160 | \(x_1\)x 1 | hash | The input is hashed twice: first with SHA-256 and then with RIPEMD-160. |

OP_CODESEPARATOR | nothing | nothing | All signature checking words will only match signatures to the data after the most recently executed OP_CODESEPARATOR. |

OP_CHECKSIG | sig, pubkey | true / false | The entire transaction’s outputs, inputs, and script (from the most recently executed OP_CODESEPARATOR to the end) are hashed. The signature used by OP_CHECKSIG must be a valid signature for this hash and public key. If it is, 1 is returned, 0 otherwise. |

Let us now demonstrate a Script example. Consider Figure bb and say that the transaction containing “Owner 0’s signature” is \(T_0\)T 0 and the transaction containing “Owner 1’s signature” is \(T_1\)T 1. Let transaction \(T_0\)T 0 contain in its output a script named scriptPubKey and let transaction \(T_1\)T 1 contain in its input a script named scriptSig. The content of the scripts is the following:

- scriptPubKey:

OP_DUP,OP_HASH160,<pubKeyHash>,OP_EQUALVERIFY,OP_CHECKSIG- scriptSig:

<sig>,<pubKey>

The data field <pubKeyHash> represents the address to which the funds are

being sent, and <pubKey> is “Owner 1’s public key”. The data field <sig> is

“Owner 1’s signature”.

We can now validate transaction \(T_1\)T 1 by following the steps in Table bd. Note that data fields are implicitly pushed on top of the stack. The transaction is valid if the stack contains true at the top and the Script interpreter has finished execution. We can see that the transaction is successfully validated. This example in fact shows one of the standard ways of validating transactions in Bitcoin.

Table bd. Script example: validation of a standard transaction.

| Stack | Script | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Empty | <sig>, <pubKey>, OP_DUP, OP_HASH160, <pubKeyHash>, OP_EQUALVERIFY, OP_CHECKSIG | scriptSig and scriptPubKey are combined. |

<sig>, <pubKey> | OP_DUP, OP_HASH160, <pubKeyHash>, OP_EQUALVERIFY, OP_CHECKSIG | Constants are pushed onto the stack. |

<sig>, <pubKey>, <pubKey> | OP_HASH160, <pubKeyHash>, OP_EQUALVERIFY, OP_CHECKSIG | Top stack item is duplicated. |

<sig>, <pubKey>, <pubHashA> | <pubKeyHash>, OP_EQUALVERIFY, OP_CHECKSIG | Top stack item is hashed. |

<sig>, <pubKey>, <pubHashA>, <pubKeyHash> | OP_EQUALVERIFY, OP_CHECKSIG | Constant is pushed onto the stack. |

<sig>, <pubKey> | OP_CHECKSIG | Equality is checked between the top two stack items. |

true | Empty | Signature is checked for the top two stack items. |

Chain of Blocks

Transactions are collected in blocks, which contain (simplified):

- transactions

- A list of new transactions recently broadcast by the network.

- hash of itself

- Each block is referenced by this hash. The implementation uses SHA-256.

- previous block

- A hash referencing the previous block.

- time

- A timestamp of the time when the block was created.

- target

- A number that determines the difficulty for the Proof-of-Work, explained below.

- nonce

- A 32-bit number that serves as the Proof-of-Work, explained below.

Nodes in the network listen for transactions and gather them into blocks. These blocks form a chain since every block contains a hash that references the previous one. The size of each block is currently limited to 4 MB.

Proof-of-Work

Imagine you receive too many unsolicited emails and you want them to stop. You publicly announce: “I will read an incoming email only if its hash starts with at least ten zero bits.” When you receive an email, you hash it and look at the bits. If the first ten are not all zero, you delete the email. You can perform such a check very quickly since hash functions are fast, and you can implement it directly in your email client.

The sender cannot check whether the hash of their email starts with ten zeroes while composing it, because whenever they change anything, the hash changes. They need to hash the final version. But what if the hash does not meet the criterion? We solve that by adding an extra field to the email’s metadata called a nonce. Since the sender cannot predict what the hash will look like with any particular nonce, their only option is to keep trying different nonces until they get a hash with at least ten leading zeroes. This essentially means they are trying to reverse the hash function — the sender knows what the output should look like and is trying to come up with an appropriate input. Since the hash function is irreversible, brute force is the only option. Once they get an email whose hash starts with at least ten zeroes, they can send it, knowing it will not be considered spam. We call the qualifying hash the Proof-of-Work (PoW) for the email. Notice that there is no need to explicitly attach the PoW since the recipient always verifies it by hashing the email. Also observe the asymmetry: generating the proof is a computationally hard problem, but checking it takes only one application of the hash function.

How many nonces, on average, does the sender need to try? Since all hash values are equally likely, having ten zero bits in a row should take \(2^{10} = 1024\)2 10 = 1024 trials on average, so anyone who wants their email read must go through the work of trying around a thousand hashes.

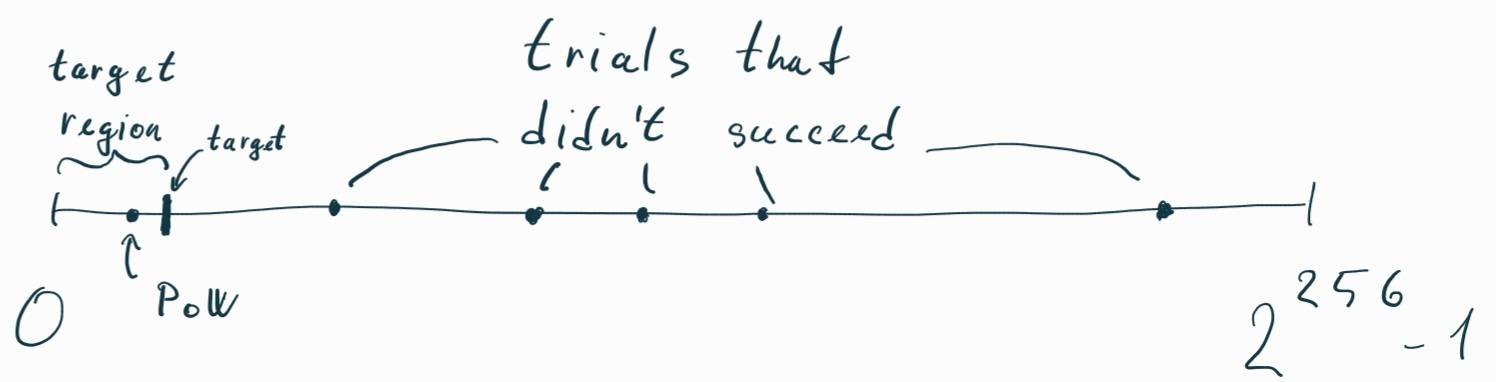

Similarly, Bitcoin nodes expect a PoW for each block. After receiving some transactions, nodes start looking for a nonce such that the hash of the whole block is less than the current target. A lower target means it is harder to mine the block because its hash needs to start with more leading zeroes, and vice versa.

Figure br illustrates the process of finding a valid PoW. We put all possible 256-bit hash outputs on an imaginary line segment, ordered by the integer values their bits represent: the zero hash on the left and the hash with all bits set to one on the right. The target determines a specific point on this line segment. The region between the zero hash and the target is where a valid PoW needs to land because all hashes in this region have enough leading zero bits. Since miners cannot predict what hash value their block will generate, their only option is to keep blindly trying nonces until they generate a block with a hash that lands below the target. In reality, the target is extremely close to the zero hash, so it takes a lot of work.

Figure br. The process of finding a valid Proof-of-Work.

If a node happens to find such a nonce, it broadcasts the block and starts working on a new one. If the node exhausts the space defined by the size of the nonce (\(2^{32}\)2 32), it can simply update the timestamp and reset the nonce. It is important to realize that the process of looking for the right nonce is memoryless. Each hash produces a random number between \(0\)0 and \(2^{256}\)2 256, so looking for the right nonce is a lottery. No matter how many nonces we have tried before, the probability of getting the right one remains the same. Thinking otherwise is the gambler’s fallacy.

The value of the target is adjusted by the network every 2016 blocks so that on average it takes about 10 minutes for the whole network to generate a new block. If blocks are being mined faster than this, each node increases the difficulty so that miners need to work harder to produce the next block. If blocks take longer than 10 minutes, each node lowers the difficulty so miners have an easier job. This balancing keeps the average time between blocks at 10 minutes as the global hash power of the network fluctuates. Not every node in the network needs to search for the right nonce. Nodes that do so are called miners.

Valid Blocks

Other nodes will accept the newly broadcast block only if all transactions in it are valid (by checking the preceding transactions as described in Chain of Transactions), and only if the hash of the block (including the right nonce) is less than the specified target (to check this, only one hash is needed). Every block contains a reference to the previous block, and therefore it is extremely difficult to change any data in previously accepted blocks. This would require re-hashing all the blocks that follow the altered one. As transactions in accepted blocks are buried under new blocks, it becomes impossible for anybody to change them. This mechanism brings complete trust to the whole history of all the blocks. It is also no longer necessary to check every preceding transaction of a new block being currently verified. It is sufficient to check just a few preceding transactions since the older ones are immutable and were already checked during their acceptance.

Decentralized Consensus

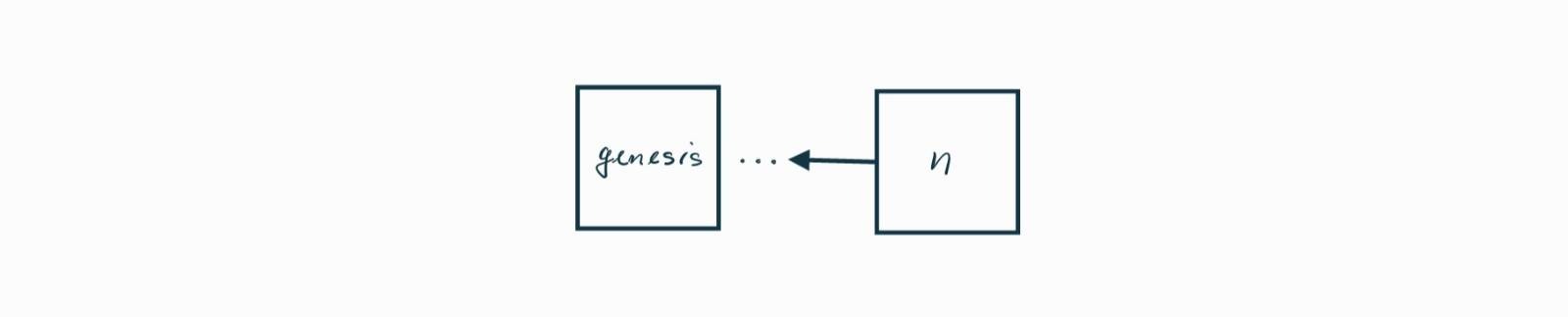

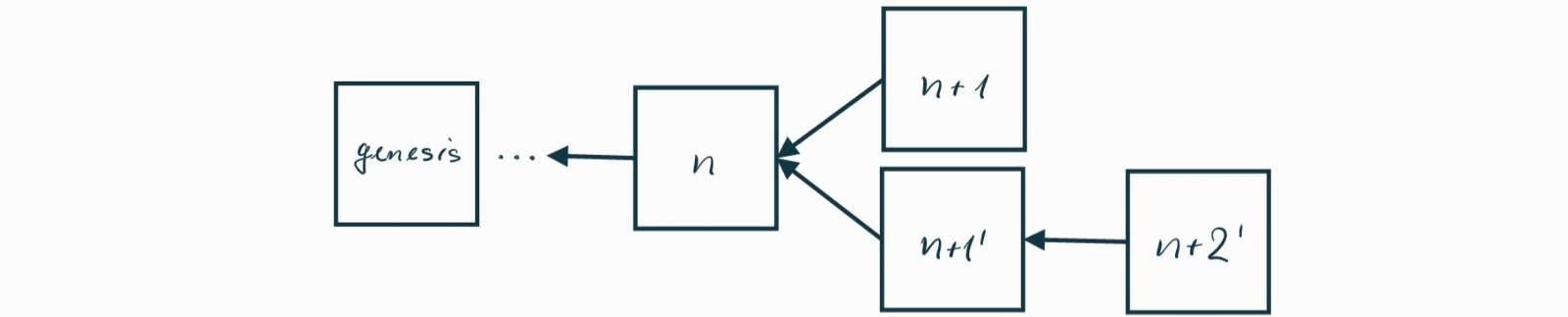

Consider the blockchain depicted in Figure bf. It starts with the genesis block and ends with block \(n\)n. Let us say that block \(n\)n is the most recent block, or in other words, the current tip of the blockchain.

Figure bf. The blockchain from the genesis block to the current tip.

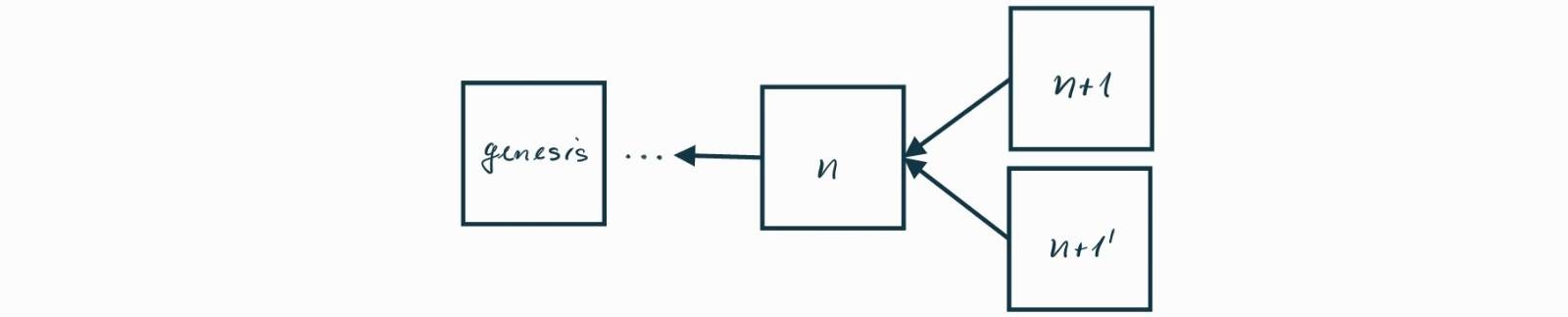

Now consider a scenario where a miner publishes a block \(n+1\)n+1, and almost at the same time, another miner publishes another block \(n+1’\)n+1’. Since both miners had the same tip \(n\)n, both new blocks reference \(n\)n as their parent, leading to a chain split. This situation is depicted in Figure bg.

Figure bg. A chain split.

It is crucial to note that blocks \(n+1\)n+1 and \(n+1’\)n+1’ can contain conflicting transactions: block \(n+1’\)n+1’ can contain a transaction that spends the same funds as a transaction in block \(n+1\)n+1. We call an attempt to spend the same funds twice double-spending.

To rule out the possibility of double-spending, all nodes in the network need to reach a decentralized consensus and collectively agree on which block to keep and which one to abandon. Abandoned blocks are called orphans. Individual nodes do not obey anyone but themselves, and yet they have to reach a collective agreement. This problem was known long before Bitcoin and was first solved in practice by Satoshi Nakamoto.

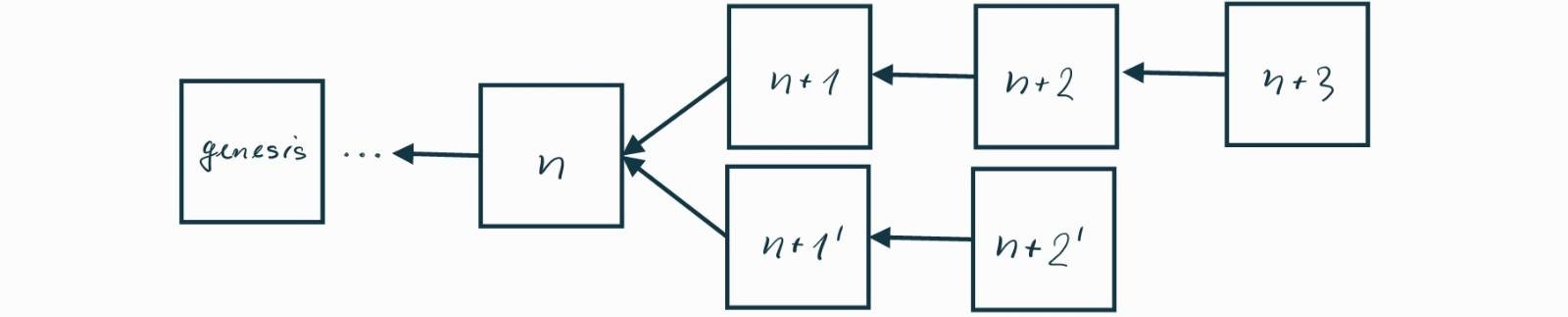

The solution is to wait and see what happens. Each node always prefers the longest chain and ignores the rest. More precisely, nodes resolve chain splits by considering the chain with the most Proof-of-Work invested to be the main one, but we can abstract that away and think of it as the longest chain. Let us see what happens when a miner appends a new block to \(n+1’\)n+1’, as depicted in Figure b8.

Figure b8. The longest chain wins.

Nodes in the network can see that the new block \(n+2’\)n+2’ extends the chain that used to end with block \(n+1’\)n+1’, so block \(n+1\)n+1 becomes an orphan and its transactions are discarded. All nodes follow this logic because each node knows what others will prefer, and that is the longest chain. Another way to see it is that the motivation for nodes to follow this rule carefully is a fear of being ignored by others. A node is free to adhere to any rules it wants, but if it starts following a chain other than what others consider the main chain, the node will be ignored, which means a loss of funds.

Imagine you are selling your computer for 1 BTC, and the current tip is at block \(n\)n. Your friend sends you the payment from their phone. The wallet generates a transaction and broadcasts it to the network. Nodes store the transaction in their mempool, a place in volatile memory where they keep unconfirmed transactions waiting for inclusion in the blockchain. Nodes share the contents of their mempools with each other, so the transaction propagates through the network.

Now say that a miner includes the transaction in block \(n+1’\)n+1’, and your node has received this block, but you have also received block \(n+1\)n+1 from another miner who did not include the transaction. You know there is a chain split and you have to wait because if block \(n+1’\)n+1’ becomes an orphan, all nodes will act as if the transaction never happened. After some time, you see block \(n+2’\)n+2’ on top of \(n+1’\)n+1’, so you hand the computer over because \(n+1’\)n+1’ became part of the longest chain and \(n+1\)n+1 became an orphan. However, consider the scenario depicted in Figure be where block \(n+1\)n+1 gets suddenly extended by two blocks \(n+2\)n+2 and \(n+3\)n+3.

Figure be. A rollback to the longer chain.

This could happen because the miner who previously produced block \(n+1\)n+1 could ignore or not receive block \(n+2’\)n+2’, and then get lucky by mining two blocks in a row. Nodes can now see that the longest chain is the one ending with \(n+3\)n+3 and perform a rollback, switching from the chain ending with \(n+2’\)n+2’ to the one ending with \(n+3\)n+3. This rollback makes blocks \(n+1’\)n+1’ and \(n+2’\)n+2’ orphaned, and the transaction of your interest gets ignored. Your friend can now spend the 1 BTC they just sent you on something else, essentially leading to double-spending since you have already given them your computer. Note that no money was created out of thin air and the overall supply was not inflated — you simply lost your money, and your friend got it back right after the purchase.

The important observation is that rollbacks will not happen indefinitely in practice. The probability of a rollback drops exponentially with each new block appended to the blockchain. Each new block makes any particular chain exponentially more difficult to re-hash and come up with an even longer alternative chain. The deeper a block is in the chain, the more immutable its data is. The solution is therefore to wait until the transaction of interest gets buried under a few blocks (called confirmations) and only then hand over the goods. As long as honest nodes control the majority of the network’s hash power, double-spending is ruled out.

Sybil Resistance

Note that Proof-of-Work is not the mechanism that directly determines what data constitutes the agreed-upon transaction history — it is the chain selection mechanism. The authority that ultimately determines the transaction history is the entity that has the ability to come up with the longest chain, and that is the majority of the mining nodes. However, PoW still plays a crucial role because the network uses it to rate-limit block creation in a Sybil-resistant way.

Sybil attacks are attacks where a single attacker spawns many fake identities and uses them to influence the attacked system. For example, one could naively base mining and chain split resolution on voting, where miners would vote on the right block using their IP address. Certain miners would then be able to gain an unfair advantage by having easy access to many IP addresses at no cost.

Proof-of-Work brings Sybil resistance because it constrains miners with real-world assets that are not effortlessly obtainable: the energy and hardware that a miner has to use to come up with the right hash. If a miner wants to scale their operations, they must invest resources in these assets just to be able to hash faster. The key to the Sybil resistance of mining is the irreversibility of the hash function.

Byzantine Fault Tolerance

A Byzantine fault is a condition in a decentralized system that can present different symptoms to different peers. For example, some nodes might act maliciously and send deceiving messages, or send different messages to different peers. Some nodes might not receive certain information due to network conditions, or even disappear from the network and show up later with an outdated state. Many such faults make different nodes have a different view of the whole network’s state, so some nodes might perform rollbacks while others do not. However, as long as the honest nodes stay in the majority, they will recover from all these faults and reach a consensus. The consensus does not hold with absolute certainty but with high probability, which is sufficient for real-world use. The reason is the probabilistic nature of any particular node having the best chain: there is always a probability of some other node showing up with a longer chain, but this probability becomes exponentially negligible with the number of blocks that would differ between the two chains.

51% Attack

It is possible to attack the Bitcoin network with enormous computational power. This attack is known as the 51% attack. If an attacker has at least 50% of the hash power of the network, they can perform rollbacks of arbitrary depth. This would not mean that they could create value out of nothing, but it would allow them to double-spend funds they recently spent in the following way:

An attacker broadcasts a transaction that pays a merchant while privately mining an alternative fork of the blockchain, in which the attacker includes a double-spent transaction or excludes the transaction sent to the merchant. The merchant sends the goods after waiting for \(n\)n confirmations (blocks). However, if the attacker has mined more than \(n\)n blocks containing the fraudulent transaction, they release their private version of the blockchain, and the network will accept this version instead of the blocks mined by honest miners. If the attacker has fewer than \(n\)n mined blocks, they simply wait until their private blockchain is longer than the one generated by honest miners and then publish it. The attacker always has the ability to do so since they control the majority of the mining power. The original transaction that was approved by the merchant will then be discarded by the network, and the merchant will not be able to use the received funds anymore.

There is an important asymmetry between the motivation to perform such an attack and the motivation not to. The motivation to perform the attack is straightforward: the attacker can manipulate the recent transaction history and benefit from double-spending. However, the attack will likely bring the price of bitcoin down, effectively reducing the value of the attacker’s loot. Furthermore, miners who participate in the attacker’s pool are likely to leave and start mining with a competing pool because they also do not want to see the value of bitcoin decrease. A loss of hash rate for the attacker then means fewer future earnings. As a result of this asymmetry, attackers are better off making a profit from honest mining instead of trying to be malicious. In other words, a successful 51% attack means sawing off the branch you are sitting on.

The hash rate of the Bitcoin network is approximately 50 exahashes of SHA-256 per second, which is an unprecedented number. The energy consumption of Bitcoin mining is a controversial topic. Miners nowadays use ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits), which is hardware that has the hash function baked directly into the silicon of its chips. Since the hardware is highly specialized, there are currently only a few companies that produce it, and they keep the design proprietary. However, similarly to mining pools, the profit model also motivates hardware producers to keep building a positive reputation instead of behaving maliciously.

Coin Mints

One bitcoin comprises \(10^8\)10 8 satoshis. One satoshi is currently the smallest unit of the Bitcoin currency, so the network actually operates solely with satoshis and not bitcoins. When a node happens to find the right nonce, it is allowed to include a special transaction that introduces new coins. Such a transaction is called a coinbase transaction. These transactions do not reference any previous transactions. At the inception of Bitcoin, each coinbase transaction was worth 50 BTC. This number keeps halving every 210,000 blocks (approximately every 4 years). This process is known as halving. The total amount of bitcoins in circulation is given by the formula \[ \sum \text{BTC} = \sum_{i=0}^{32} \frac{210{,}000 \left\lfloor \frac{50 \cdot 10^8}{2^i} \right\rfloor}{10^8}. \] This is a geometrically decreasing sequence, meaning that the final amount of bitcoins in circulation will not exceed 21 million. The coinbase transaction also motivates miners to support the network and spend their resources on hashing. A node that creates a new block can also claim the difference between total inputs and total outputs of the included transactions. This difference is called the transaction fee, and users can motivate miners to process their transactions with higher priority by providing a higher fee. Fees also prevent spam transactions. If transactions had no cost, a malicious entity could keep publishing an enormous amount of them by sending bitcoin back to themselves. All blocks have a limited size, and since miners would have no means to distinguish such transactions from legitimate ones, the spam would occupy a significant portion of the block space, leading to a denial-of-service attack. During the first few years, there were usually no fees associated with transactions. As the transaction volume grew, fees became the norm, and transactions with no fees are simply ignored. It is also expected that fees will be the main incentive for miners once the predetermined number of coins have entered circulation.

Let us call the global hashing power of all miners in the network the hash rate. Since nodes always adjust the target so that it takes about 10 minutes to generate a new block, the higher the network’s hash rate, the less likely it is for an individual miner to generate a block, and vice versa. This means that miners compete with each other for the reward, and the more hashing power an individual miner has, the more likely they are to win. Miners nowadays unite their hashing power under mining pools since the probability of finding the right hash for a single miner is very low. A mining pool is a node that prepares new blocks ready for inclusion in the blockchain but missing a PoW. The pool sends these blocks to individual miners, who do not create blocks but only run their hashing hardware to find a nonce that leads to a valid PoW. Once such a miner finds a nonce, they send the complete block back to the pool, which then broadcasts it to the network.

The pool distributes the block reward to the individual miners who participated in the hashing process, and even miners who did not manage to find the PoW get paid based on how much hash rate they provided. The pool can easily measure the hash rate of an individual miner by periodically asking them to submit the block they are working on and checking how close the hash is to the target region. Each submitted block contains a coinbase transaction with the receiver’s address set to the pool’s address. Note that at some point, one of the miners generates a hash that is not only close to the target but actually below it. Also note that once a miner finds such a hash, they cannot simply change the coinbase transaction to point to their own address since doing so would invalidate the hash.

The motivation for miners to join a pool is pragmatic: it lets them get paid frequently and regularly. The probability that a miner mines the next block is proportional to the miner’s share of the whole network’s hash rate. Non-industrial miners can afford only a negligible fraction, so if they mined on their own, they would need to wait for weeks or even years before mining a block. By joining a pool that mines at least one block per day, they can receive daily payments.

Soft Forks and Hard Forks

When a node receives a block, it performs a series of checks to ensure the block is valid, discarding it otherwise. We call these checks the consensus rules. Whenever the consensus rules are modified, we introduce either a so-called soft fork or a hard fork. Such changes are always introduced in a new version of the node software. Since nobody can force anyone to run a particular version, all changes require consent from node operators. If some nodes adopt the new rules while others do not, there will be a permanent chain split at the height where the change took effect, and both groups will end up with their own branch of the original blockchain. Most likely, each group will give their chain a different name, resulting in two different cryptocurrencies sharing a common history before the split.

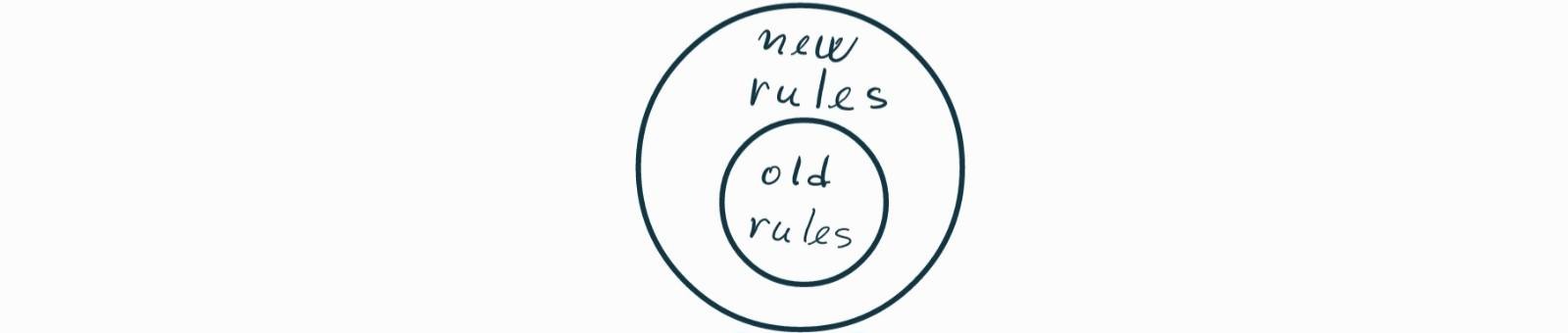

A soft fork restricts the consensus rules, so the updated set becomes a strict subset of the original set, as depicted in Figure bj. Soft forks are backward compatible: the original nodes will keep accepting all blocks accepted by the updated nodes. If the majority of the mining nodes adopt the soft fork, the whole network will keep reaching consensus, and blocks created by the original nodes that fall outside the updated rules will keep becoming orphaned. However, if the updated mining nodes stay in the minority, the original and updated nodes in the network will each end up with their own chain.

Figure bj. A soft fork restricts the consensus rules.

A hard fork relaxes the consensus rules, so the updated set becomes a strict superset of the original set, as depicted in Figure bu. If the original mining nodes stay in the majority, blocks from the updated nodes that fall outside the original rules will keep becoming orphaned. If the updated nodes become the mining majority, there will be a chain split unless all nodes, including non-mining ones, switch to the new rules. The reason is that non-mining nodes also need to accept blocks complying with the new set of consensus rules.

Figure bu. A hard fork relaxes the consensus rules.

The main difference is that in order to avoid a chain split, a hard fork requires every node in the network to adopt it, while a soft fork requires adoption only from the majority of the mining nodes.

Blockchain Size

The actual implementation hashes the transactions into a Merkle tree. This is an optimization to allow verification of payments without storing the transactions. This avoids using the whole blockchain, the size of which at the time of writing is about 200 GB. The growth is naturally linear at the rate of approximately 50 GB per year. Merkle trees are also useful for maintaining the integrity (by providing hash checks) of the whole blockchain since it is distributed around the world.

For a Bitcoin light client, it is sufficient to keep only the root hash of the Merkle tree. If such a client needs to verify a transaction, it can link it to a place in the chain according to its timestamp and check that other full nodes accepted it. This method is called Simplified Payment Verification (SPV). However, light clients are vulnerable to second preimage attacks (an attacker could forge the interior of the Merkle tree). Also note that if a user does not wish to share which transactions are of interest to them, they have to run a full node (and store the whole blockchain) since light clients request specific transactions from other nodes.

Scalability

A drawback not mentioned in the original paper is that the Bitcoin network is not able to process an arbitrary amount of transactions over a certain period of time. The difficulty is adjusted every 2016 blocks so that it takes about 10 minutes for the whole network to generate a new block. The difficulty is given by the value of the target, which is a 256-bit number. This value is stored in each block in the “Bits” field, the size of which is 4 bytes. The first byte is the exponent \(e\)e and the remaining three bytes constitute the mantissa \(m\)m. The value of the target is then calculated according to the formula \[ \text{target} = 256^{e-3} \cdot m. \] The target is adjusted every 2016 blocks so that \[ \text{target}_{\text{new}} = \text{target}_{\text{previous}} \cdot \frac{\delta}{2 \text{ weeks}}, \] where \(\delta\) is the actual time difference between the 2016 blocks.

Every block can contain only a limited amount of transactions. Based on this, it is possible to estimate that the network is able to process only about 7 transactions per second worldwide. This issue is currently being addressed by introducing another layer of transactions over the original blockchain. This solution is called the Lightning Network (Poon and Dryja 2016).

Broader Outlook

The initial ideas and purposes of Bitcoin as described in (Nakamoto 2008) can be extended to various other fields. For example, since transactions can contain a certain amount of arbitrary data, we can store this data in the blockchain. Since we can think of the blockchain as an immutable distributed public database, this data will be immutably and publicly stored around the world for as long as humanity does not lose its computers. If we store a hash of a photograph of a contract with a counterparty in the blockchain at a certain time, the counterparty will never be able to deny the existence of the document after this time. A demonstration of this possibility is the famous message that Satoshi Nakamoto left in the genesis block:

“The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

The message proves that the block could not have been created earlier than 3 January 2009. It is the headline of the British national newspaper The Times.

Another popular extension of the blockchain is the use of smart contracts (Buterin 2014).

The Proof-of-Work algorithm by which Bitcoin achieves distributed consensus can be changed to a different one called Proof-of-Stake (PoS) (Buterin 2013), which doesn’t inherently require computational power.

Epilogue

It is natural that Bitcoin attracts the attention of not only computer science and cryptography enthusiasts but also politicians and economists, since it brings a new level of freedom and responsibility to human society. Bitcoin has the potential to reduce the power of governments as it lies beyond the control of central banks. It also raises the question of whether the energy demands of the Proof-of-Work are worth it given the current environmental situation.

There are economists who say that Bitcoin will inevitably vanish since it has nothing to offer, and there is no real value behind it. There are also people from the same field who claim that Bitcoin is going to change the world completely. Some see it as a great store of value while others don’t trust it at all. There are many philosophical stances people adopt on Bitcoin, spanning the whole spectrum of both positive and negative radical opinions.

Since the Bitcoin codebase is open source, anyone can fork the source code in the software engineering sense and start either a completely new chain of blocks from the very beginning or fork the existing Bitcoin blockchain at a specific point and continue in its own way. In both cases, a new cryptocurrency is created since the new blocks are not compatible with the Bitcoin blockchain anymore. In the latter case, users can keep and use all the funds they owned in the standard Bitcoin blockchain. There are currently thousands of such cryptocurrencies. This demonstrates the voluntary nature of Bitcoin since anyone can use (including operating a full node or mining) any chain of blocks they prefer. Operators running Bitcoin nodes and miners decide by themselves what version of the blockchain they run, and nobody can force them otherwise. The same holds for ordinary Bitcoin users and programmers who propose and develop new features.

This brings us to an open question that some people might ask: what determines the price of bitcoin? The answer is probably simpler than some may expect — it is the willingness of others to acquire it. Bitcoin is currently considered quite volatile. It is expected that potential future adoption by the masses will make it much more stable. Let us conclude with a quote by the mysterious creator of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto, from 14 February 2010 (Nakamoto 2010):

“I’m sure that in 20 years there will either be very large transaction volume or no volume.”

References

See the Chain of Blocks section. ↩︎

The difference between total inputs and total outputs serves as an incentive for miners. See Coin Mints. ↩︎