Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Airman’s Odyssey

AES is one of the most widely used block ciphers for symmetric encryption. The cipher was originally named Rijndael, after its designers Joan Daemen and Vincent Rijmen. In 1997, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) announced the development of AES and organized an open competition, which Rijndael won. NIST published the cipher as the Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 197 (Pub 2001) in 2001. AES superseded the previous Data Encryption Standard (DES).

Structure

AES is thoroughly described in (Pub 2001), with further information in (Daemen and Rijmen 2002).

AES is a symmetric block cipher with a block size of 128 bits. Three key sizes are possible: 128, 192, and 256 bits. The original Rijndael cipher is more flexible, allowing both block and key sizes to be any multiple of 32 bits in the range 128 to 256 independently. This is the only difference between Rijndael and AES. We focus solely on AES-128, the version with both block and key size set to 128 bits. This restriction has almost no impact on generality since the structure of all variants remains the same up to certain constants. A smaller-scale variant is defined in a subsequent section.

The input and output of the cipher are one-dimensional arrays of 16 bytes. The cipher operates on a two-dimensional \(4 \times 4\)4 4 array of 16 bytes called the state.

Figure r6. The state array of \(\mathrm{SR}(n, 4, 4, e)\)SR(n, 4, 4, e).

Remark d5. Bytes in the state can be considered as polynomials of the form \[\sum_{i=0}^{7} b_i x^i,\] where \(b_i \in \mathbb{F}_2\)b i F 2 are the individual bits, see Remark bz. These polynomials are the elements of the quotient ring \(\mathbb{F}_2[x] / \langle f(x) \rangle\)F 2[x] / f(x) , where \(f(x) = x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x + 1 \in \mathbb{F}_2[x]\)f(x) = x 8 + x 4 + x^3 + x + 1 F_2[x] is irreducible over \(\mathbb{F}_2[x]\)F 2[x], so the quotient ring is a finite field — as described in Example du and Proposition nz. We denote this finite field by \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)GF(2 8).

Remark dh. A byte can also be described by its hexadecimal value, e.g. \(63_{16}\)63 16 represents \(01100011_2\)01100011 2, or as described in the previous remark, \(03_{16}\)03 16 represents the polynomial \(x + 1\)x + 1. A byte can also be regarded as a vector in an 8-dimensional vector space over \(\mathrm{GF}(2)\)GF(2). We employ all these views on bytes throughout. Moreover, a word consisting of four bytes can be regarded as a vector in a 4-dimensional vector space over \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)GF(2 8).

The overall structure of the cipher is described in Algorithm d7. The initial key is expanded into 44 words (176 bytes), which are then used throughout the encryption. This expansion is described in Algorithm ry. The plaintext is copied into the state and the initial key addition is performed. The cipher then performs a cycle with nine iterations called rounds. The tenth round omits the MixColumns operation. This omission is due to the design of the inverse cipher — it makes the structure of the inverse cipher more consistent with the structure described in Algorithm d7. The inverse cipher is described in (Pub 2001). All operations that manipulate the state have inverse counterparts, and the inverse cipher applies these in reverse order with a reversed key schedule.

A prime on a variable (e.g. \(c’\)c’) denotes the updated value. Each byte in the state has two indices: the row index \(0 \le r < 4\)0 r < 4 and the column index \(0 \le c < 4\)0 c < 4, so that a specific byte is denoted \(s_{r,c}\)s r,c.

Algorithm d7. AES (Pub 2001).

Input: a 16-byte array plaintext, a 16-byte array key.

Output: a 16-byte ciphertext array state.

- \(\mathit{expKey} \gets \mathrm{ExpandKey}(\mathit{key})\)expKey ExpandKey(\mathit{key}).

- \(\mathit{state} \gets \mathit{plaintext}\)state plaintext.

- \(\mathit{state} \gets \mathrm{AddRoundKey}(\mathit{state}, \mathit{expKey}[0:3])\)state AddRoundKey(\mathit{state}, \mathit{expKey}[0:3]).

- for \(\mathit{round} \gets 1\)round 1 to \(9\)9:

- \(\mathit{state} \gets \mathrm{MixColumns}(\mathrm{ShiftRows}(\mathrm{SubBytes}(\mathit{state})))\)state MixColumns(\mathrm{ShiftRows}(\mathrm{SubBytes}(\mathit{state}))).

- \(\mathit{state} \gets \mathrm{AddRoundKey}(\mathit{state}, \mathit{expKey}[4 \cdot \mathit{round} : 4(\mathit{round} + 1) - 1])\)state AddRoundKey(\mathit{state}, \mathit{expKey}[4 \cdot \mathit{round} : 4(\mathit{round} + 1) - 1]).

- \(\mathit{state} \gets \mathrm{ShiftRows}(\mathrm{SubBytes}(\mathit{state}))\)state ShiftRows(\mathrm{SubBytes}(\mathit{state})).

- \(\mathit{state} \gets \mathrm{AddRoundKey}(\mathit{state}, \mathit{expKey}[40:43])\)state AddRoundKey(\mathit{state}, \mathit{expKey}[40:43]).

- return \(\mathit{state}\)state.

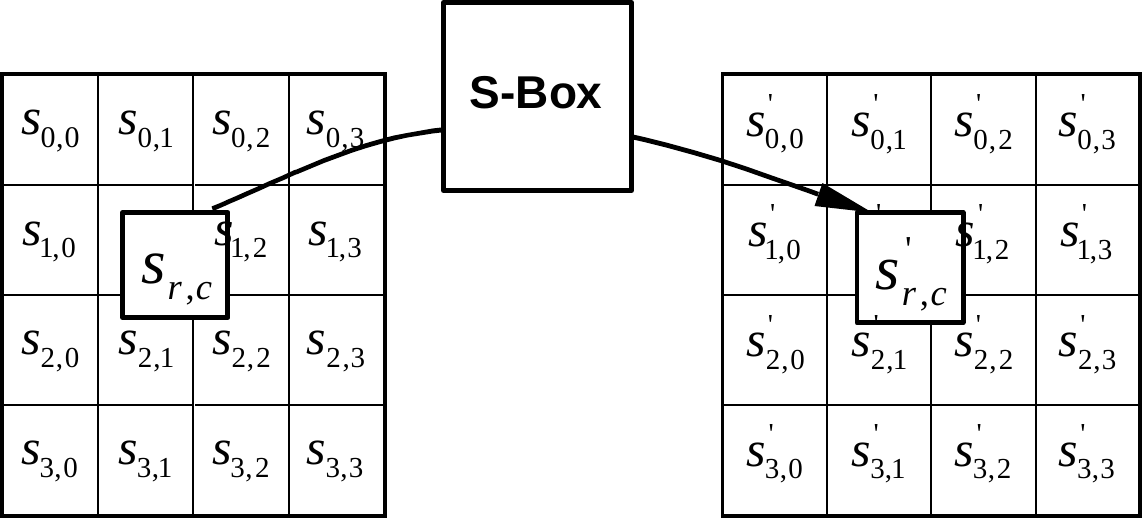

SubBytes

This transformation operates on the individual bytes of the state.

Definition d6. The S-box is a composition of the following two transformations:

- Take the multiplicative inverse in \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)GF(2 8); the element \(00_{16}\)00 16 is mapped to itself.

- Apply the following affine transformation over \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)GF(2 8): \[b_i’ = b_i \oplus b_{(i+4) \bmod 8} \oplus b_{(i+5) \bmod 8} \oplus b_{(i+6) \bmod 8} \oplus b_{(i+7) \bmod 8} \oplus c_i,\] for \(0 \le i < 8\)0 i < 8, where \(c = 63_{16}\)c = 63 16 and \(b_i \in \mathrm{GF}(2)\)b i GF(2).

The affine transformation can also be expressed in matrix notation:

\[\begin{pmatrix} b_0’ \\ b_1’ \\ b_2’ \\ b_3’ \\ b_4’ \\ b_5’ \\ b_6’ \\ b_7’ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} b_0 \\ b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3 \\ b_4 \\ b_5 \\ b_6 \\ b_7 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}. \tag{d9}\]

The S-box is the only non-linear transformation in AES. It can be implemented as a look-up table containing the substitution values for each byte in \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)GF(2 8).

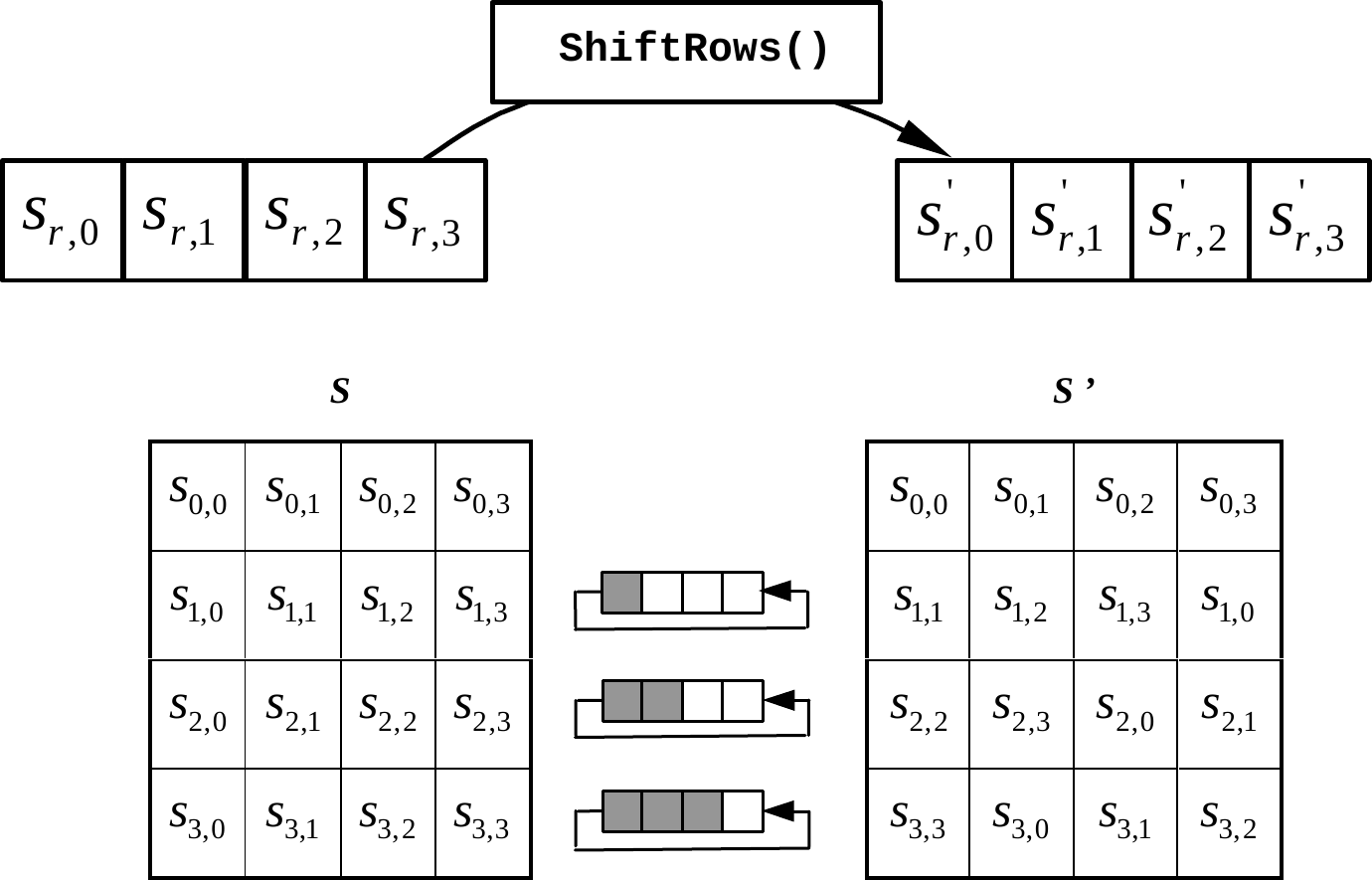

ShiftRows

This transformation operates on the individual rows of the state. It is defined by \[s’_{r,c} = s_{r, (r+c) \bmod 4} \quad \text{for} \quad 0 < r < 4 \quad \text{and} \quad 0 \le c < 4.\] Each row \(i\)i of the state is cyclically rotated to the left by \(i\)i bytes, where \(0 \le i < 4\)0 i < 4, so the first row remains unchanged and the fourth row is rotated by three bytes.

The ShiftRows operation is a linear transformation. A cyclic rotation by one position of a vector of length four can be represented by the matrix

\[R_4 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix}. \tag{rd}\]

Rotations by more positions can be obtained by taking higher powers of \(R_4\)R 4. If \(r_i\)r i represents the \(i\)i-th row of the state, the ShiftRows operation is given by

\[\begin{pmatrix} r_0’ \\ r_1’ \\ r_2’ \\ r_3’ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} I & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & R_4 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & R_4^2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & R_4^3 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} r_0 \\ r_1 \\ r_2 \\ r_3 \end{pmatrix}. \tag{rr}\]

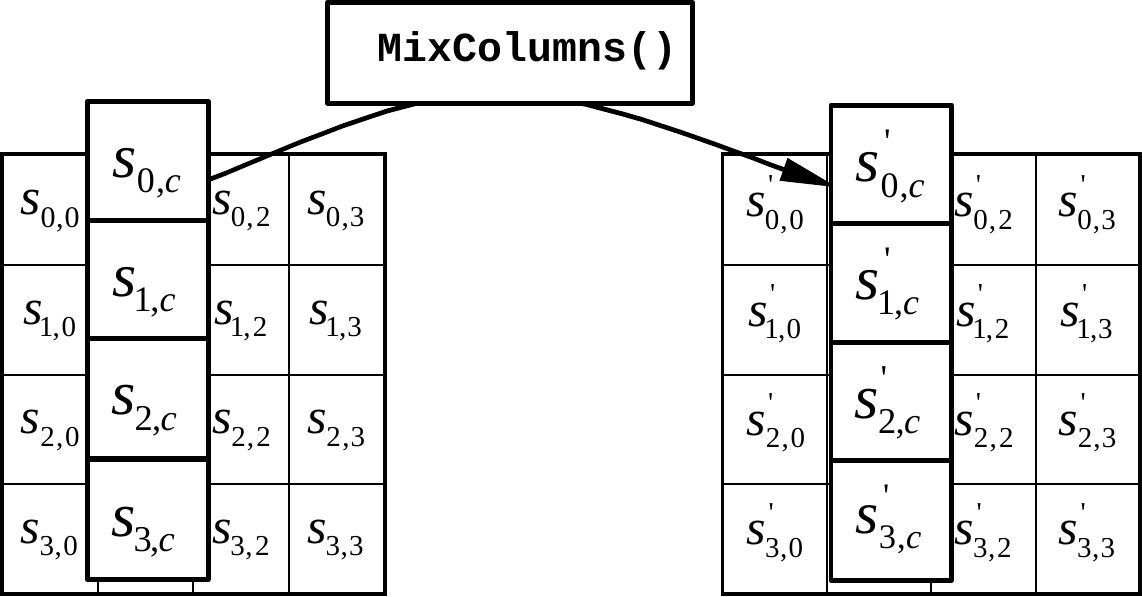

MixColumns

This transformation operates on the individual columns of the state. Each column is considered as a four-term polynomial whose coefficients are the four bytes of the column, regarded as elements of \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)GF(2 8). Each column is multiplied modulo \(x^4 + 1\)x 4 + 1 with the polynomial \[a(x) = 03_{16} \, x^3 + 01_{16} \, x^2 + 01_{16} \, x + 02_{16} \in \mathrm{GF}(2^8)[x].\] The multiplication is performed as in Example du.

The coefficients were chosen so that MixColumns is fast on 8-bit architectures. The constant \(01_{16}\)01 16 requires no processing, polynomial multiplication by \(02_{16}\)02 16 can be implemented by a shift and a conditional XOR, and multiplication by \(03_{16}\)03 16 can be implemented as multiplication by \(02_{16}\)02 16 and an additional XOR.

The polynomial \(x^4 + 1\)x 4 + 1 is not irreducible over \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)[x]\)GF(2 8)[x] since \(x^4 + 1 = (x^2 + 1)(x^2 + 1)\)x 4 + 1 = (x 2 + 1)(x^2 + 1). The quotient ring \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)[x] / \langle x^4 + 1 \rangle\)GF(2 8)[x] / x 4 + 1 is therefore not a finite field, so not every element has a multiplicative inverse. However, the polynomial \(a(x)\)a(x) does have its multiplicative inverse, namely \[a^{-1}(x) = 0\mathrm{B}_{16} \, x^3 + 0\mathrm{D}_{16} \, x^2 + 09_{16} \, x + 0\mathrm{E}_{16},\] so the MixColumns operation remains invertible.

Remark rg. Let \(b(x) = b_3 x^3 + b_2 x^2 + b_1 x + b_0\)b(x) = b 3 x 3 + b_2 x^2 + b_1 x + b_0 and \(c(x) = c_3 x^3 + c_2 x^2 + c_1 x + c_0\)c(x) = c 3 x 3 + c_2 x^2 + c_1 x + c_0 be two polynomials in \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)[x]\)GF(2 8)[x]. Addition consists of adding the coefficients of like powers of \(x\)x. These coefficients are elements of \(\mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)GF(2 8), so addition effectively corresponds to XOR, denoted \(\oplus\): \[b(x) + c(x) = (b_3 \oplus c_3) x^3 + (b_2 \oplus c_2) x^2 + (b_1 \oplus c_1) x + (b_0 \oplus c_0).\] As in Example du, multiplication modulo \(m(x) = x^4 + 1\)m(x) = x 4 + 1 is performed in two stages. First, compute the full product \(b(x) c(x) = d(x)\)b(x) c(x) = d(x) where \[d(x) = d_6 x^6 + d_5 x^5 + d_4 x^4 + d_3 x^3 + d_2 x^2 + d_1 x + d_0\] with \[\begin{aligned} d_0 &= b_0 c_0, \\ d_1 &= b_1 c_0 \oplus b_0 c_1, \\ d_2 &= b_2 c_0 \oplus b_1 c_1 \oplus b_0 c_2, \\ d_3 &= b_3 c_0 \oplus b_2 c_1 \oplus b_1 c_2 \oplus b_0 c_3, \\ d_4 &= b_3 c_1 \oplus b_2 c_2 \oplus b_1 c_3, \\ d_5 &= b_3 c_2 \oplus b_2 c_3, \\ d_6 &= b_3 c_3. \end{aligned}\] Then divide \(d(x)\)d(x) by \(m(x)\)m(x) to obtain the quotient \(q(x)\)q(x) and remainder \(r(x)\)r(x): \[d(x) = q(x) m(x) + r(x)\] where \(q(x) = d_6 x^2 + d_5 x + d_4\)q(x) = d 6 x 2 + d_5 x + d_4 and \(r(x) = r_3 x^3 + r_2 x^2 + r_1 x + r_0\)r(x) = r 3 x 3 + r_2 x^2 + r_1 x + r_0 with

\[\begin{aligned} r_0 &= b_0 c_0 \oplus b_3 c_1 \oplus b_2 c_2 \oplus b_1 c_3, \\ r_1 &= b_1 c_0 \oplus b_0 c_1 \oplus b_3 c_2 \oplus b_2 c_3, \\ r_2 &= b_2 c_0 \oplus b_1 c_1 \oplus b_0 c_2 \oplus b_3 c_3, \\ r_3 &= b_3 c_0 \oplus b_2 c_1 \oplus b_1 c_2 \oplus b_0 c_3. \end{aligned} \tag{r8}\]

The coefficients \(r_i\)r i can be expressed in matrix notation:

\[\begin{pmatrix} r_0 \\ r_1 \\ r_2 \\ r_3 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} b_0 & b_3 & b_2 & b_1 \\ b_1 & b_0 & b_3 & b_2 \\ b_2 & b_1 & b_0 & b_3 \\ b_3 & b_2 & b_1 & b_0 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} c_0 \\ c_1 \\ c_2 \\ c_3 \end{pmatrix}. \tag{re}\]

We take the remainder \(r(x)\)r(x) as the result, so \(b(x) c(x) \equiv r(x) \pmod{m(x)}\)b(x) c(x) r(x) m(x). We consider \(b(x)\)b(x) as a fixed polynomial and use its coefficients to fill the matrix.

Remark rg shows that multiplication by a fixed polynomial modulo another fixed polynomial is a linear transformation, so MixColumns is a linear transformation as well. As shown in Remark dh, the coefficients \(03_{16}\)03 16, \(02_{16}\)02 16, and \(01_{16}\)01 16 of the polynomial \(a(x) \in \mathrm{GF}(2^8)[x]\)a(x) GF(2 8)[x] can be written as the polynomials \(x + 1\)x + 1, \(x\)x, and \(1\)1, respectively. Associating \(a(x)\)a(x) with \(b(x)\)b(x) from the remark, we get

\[\begin{pmatrix} s_{0,c}’ \\ s_{1,c}’ \\ s_{2,c}’ \\ s_{3,c}’ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} x & x+1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & x & x+1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & x & x+1 \\ x+1 & 1 & 1 & x \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} s_{0,c} \\ s_{1,c} \\ s_{2,c} \\ s_{3,c} \end{pmatrix} \tag{rj}\] for \(0 \le c < 4\)0 c < 4. This expression fully describes the MixColumns operation.

Key Schedule

The AddRoundKey transformation takes in four words (16 bytes) of the expanded key and adds them to the state. Each word (4 bytes) is added to a column of the state:

\[(s’_{0,c}, s’_{1,c}, s’_{2,c}, s’_{3,c})^T = (s_{0,c}, s_{1,c}, s_{2,c}, s_{3,c})^T \oplus (\mathit{expKey}_{4 \cdot \mathit{round} + c})^T \tag{rk}\] for \(0 \le c < 4\)0 c < 4. The value of \(\mathit{round}\)round is 0 during the initial addition and 10 during the last addition.

The values of the expanded key are defined by Algorithm ry. The initial key is copied into the first four words of \(\mathit{expKey}\)expKey. Each following word is the XOR of the previous word and the word four positions earlier. For words in positions that are multiples of four, a transformation is applied to the previous word before the XOR.

The RotWord operation takes a four-byte word \((x_0, x_1, x_2, x_3)^T\)(x 0, x 1, x_2, x_3)^T and produces the cyclically rotated word \((x_1, x_2, x_3, x_0)^T\)(x 1, x 2, x_3, x_0)^T. The SubWord operation takes a four-byte word and applies the S-box to each byte. The round constant array \(\mathit{Rcon}[j]\)Rcon[j] contains ten four-byte words defined by \((02_{16}^{j-1}, 00_{16}, 00_{16}, 00_{16})^T\)(02 16 j-1, 00_{16}, 00_{16}, 00_{16})^T, where the only effective part is the first byte \(02_{16}^{j-1} \in \mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)02 16 j-1 {GF}(2^8) (i.e., \(x^{j-1} \in \mathrm{GF}(2^8)\)x j-1 GF(2 8)).

Algorithm ry. Key Schedule for AES (Pub 2001).

Input: a 16-byte array key.

Output: a 44-word (176-byte) key schedule expKey.

- for \(i \gets 0\)i 0 to \(3\)3:

- \(\mathit{expKey}[i] \gets \mathrm{word}(\mathit{key}[4i], \mathit{key}[4i+1], \mathit{key}[4i+2], \mathit{key}[4i+3])\)expKey[i] word(\mathit{key}[4i], \mathit{key}[4i+1], \mathit{key}[4i+2], \mathit{key}[4i+3]).

- for \(i \gets 4\)i 4 to \(43\)43:

- \(\mathit{tmp} \gets \mathit{expKey}[i-1]\)tmp expKey[i-1].

- if \(i \equiv 0 \pmod{4}\)i 0 4:

- \(\mathit{tmp} \gets \mathrm{SubWord}(\mathrm{RotWord}(\mathit{tmp})) \oplus \mathit{Rcon}[i/4]\)tmp SubWord(\mathrm{RotWord}(\mathit{tmp})) \oplus \mathit{Rcon}[i/4].

- \(\mathit{expKey}[i] \gets \mathit{expKey}[i-4] \oplus \mathit{tmp}\)expKey[i] expKey[i-4] \oplus \mathit{tmp}.

- return \(\mathit{expKey}\)expKey.

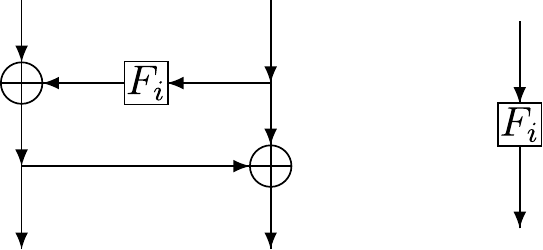

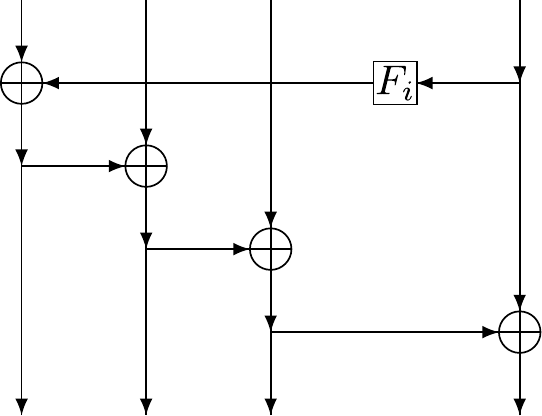

Figure rm depicts four iterations of the loop in step 2 of Algorithm ry. Each vertical line represents a four-byte word in the \(\mathit{expKey}\)expKey array. The box containing the transformation \(F_i\)F i corresponds to the conditional in step 2 of Algorithm ry.

Figure rm. Key schedule schematic (Cid, Murphy, and Robshaw 2005).

Small Scale Variants

Before defining scaled-down derivatives of AES, consider how long a brute-force attack on AES-128 would take. Suppose we have a computer cluster with ten billion nodes, each running at 3.3 GHz, and that one AES-128 encryption takes a single clock cycle per node. With around \(3 \cdot 10^7\)3 10 7 seconds per year, the cluster would test \(3 \cdot 10^7 \cdot 3.3 \cdot 10^9 \cdot 10^{10} \approx 10^{27} \approx 2^{90}\)3 10 7 3.3 10 9 \cdot 10^10 \approx 10^27 \approx 2^{90} keys per year. In the worst case, guessing the correct key would take around \(2^{38}\)2 38 years — about 250 billion, while the age of the universe is estimated at around 13.8 billion years. Now suppose that the average consumption of each node is only 1 W and that 1 kWh of energy costs only 0.01 EUR (the average price of 1 kWh for European household consumers is around 0.2 EUR in 2020). The energy cost of such an attack would be approximately \(10^{20}\)10 20 EUR.

This infeasibility motivated researchers to develop scaled-down versions of the cipher to provide manageable insight into its internals. Carlos Cid et al. introduced such versions in (Cid, Murphy, and Robshaw 2005) and (Cid, Murphy, and Robshaw 2006). The reductions emerge naturally and the cipher is described by the following parameters:

- the number of rounds \(n\)n, \(1 \le n \le 10\)1 n 10;

- the number of rows \(r\)r of the state, \(r = 1, 2, 4\)r = 1, 2, 4;

- the number of columns \(c\)c of the state, \(c = 1, 2, 4\)c = 1, 2, 4;

- the number of bits \(e\)e of the elements of the state, \(e = 4, 8\)e = 4, 8.

We denote the scaled-down version by \(\mathrm{SR}(n, r, c, e)\)SR(n, r, c, e). AES-128 is then \(\mathrm{SR}(10, 4, 4, 8)\)SR(10, 4, 4, 8) with one difference: the last round of \(\mathrm{SR}\)SR retains MixColumns, whereas AES-128 omits it. Since MixColumns is a linear transformation, the overall complexity of cryptanalysis remains the same — a solution for one cipher provides a solution for the other.

The cipher operates over \(\mathrm{GF}(2^e)\)GF(2 e), defined by \(\mathbb{F}_2[x] / \langle f(x) \rangle\)F 2[x] / f(x) where \(f(x) = x^4 + x + 1\)f(x) = x 4 + x + 1 when \(e = 4\)e = 4 and \(f(x) = x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x + 1\)f(x) = x 8 + x 4 + x^3 + x + 1 when \(e = 8\)e = 8. The polynomial \(f(x)\)f(x) is irreducible over \(\mathbb{F}_2[x]\)F 2[x] in both cases, and for \(e = 8\)e = 8, it is identical to the polynomial used in AES-128.

Scaled SubBytes

The SubBytes operation is identical to AES-128 when \(e = 8\)e = 8. When \(e = 4\)e = 4, it is a composition of the following two transformations:

- Take the multiplicative inverse in \(\mathrm{GF}(2^4)\)GF(2 4); the element \(0_{16}\)0 16 is mapped to itself.

- Apply the following affine transformation over \(\mathrm{GF}(2^4)\)GF(2 4):

\[\begin{pmatrix} b_0’ \\ b_1’ \\ b_2’ \\ b_3’ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} b_0 \\ b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}. \tag{rc}\]

Scaled ShiftRows

The ShiftRows operation cyclically rotates row \(i\)i of the state by \(i\)i positions, \(0 \le i < r - 1\)0 i < r - 1. When \(r = 4\)r = 4, we use the matrix \(R_4\)R 4 from equation rd. When \(r = 2\)r = 2, the rotation matrix becomes \[R_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}.\] When \(c = 4\)c = 4, we use the matrix from equation rr, substituting \(R_2\)R 2 for \(R_4\)R 4 when \(r = 2\)r = 2. When \(c = 2\)c = 2, the expression becomes

\[\begin{pmatrix} r_0’ \\ r_1’ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} I & 0 \\ 0 & R \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} r_0 \\ r_1 \end{pmatrix} \tag{rp}\] where \(R\)R is either \(R_4\)R 4 or \(R_2\)R 2 and \(I\)I is the identity matrix of corresponding size. When \(r = 1\)r = 1 or \(c = 1\)c = 1, the operation has no effect since either \(R_2\)R 2 becomes \((1)\)(1) or the matrix becomes \(I\)I.

Scaled MixColumns

The MixColumns operation is identical to AES-128 when \(r = 4\)r = 4. When \(r = 2\)r = 2, it is defined by the following linear transformation:

\[\begin{pmatrix} s_{0,j}’ \\ s_{1,j}’ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} x+1 & x \\ x & x+1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} s_{0,j} \\ s_{1,j} \end{pmatrix} \tag{rq}\] for \(0 \le j < 2\)0 j < 2, similarly to equation rj for AES-128. When \(r = 1\)r = 1, the operation has no effect.

Scaled Key Schedule

When \(c = 4\)c = 4, the cipher uses the same key schedule as AES-128. For \(c = 2\)c = 2 and \(c = 1\)c = 1, the structure is naturally reduced. Similarly to AES-128, AddRoundKey takes in \(c\)c words of length \(r\)r, where each word contains elements of \(\mathrm{GF}(2^e)\)GF(2 e). These elements are added to the state as in equation rk. The RotWord and SubWord operations take \(r\)r-tuples of elements of \(\mathrm{GF}(2^e)\)GF(2 e). The round constant array contains \(r\)r-tuples in which the only non-zero element is the first one, namely \(x^{j-1} \in \mathrm{GF}(2^e)\)x j-1 GF(2 e) where \(j\)j is the round number. The initial key has \(rce\)rce bits and is added to the plaintext before starting the encryption and generating the subsequent sub-keys.

Figure rx. Scaled-down key schedule (Cid, Murphy, and Robshaw 2005).